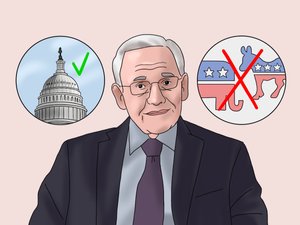

How to Be an Investigative Journalist

Authored by

Investigative JournalistAs a journalist, your duty is to uncover the best obtainable version of the truth through evidence, sources, and testimony. This process is broken down by a man who’s considered one of the greatest journalists of our time, Bob Woodward.